Until recently, majority opinion designated men responsible for the masterful early paintings adorning cavernous walls around the world. There wasn’t much science behind the assumption, just that general air of androcentrism that presumes men play a central role in just about everything.

Things changed a little, however, in the 1970s and ‘80s, when male and female archaeologists began challenging the many male-centric inferences throughout science and history.

“The point that was made was quite simple,” archaeologist Dave Whitley of ASM Affiliates explained to The Huffington Post. “How do we know that the cave artists were males? Frankly, we don’t! The presumption that somehow they must be was just that — it was speculation, and there was no real data one way or the other that told us which gender was responsible.”

Whitley is a California-based archaeologist specializing in prehistoric rock art and cave art, working primarily with North American caves as well as caves in South Africa, France and Spain. While Whitley isn’t sure that women are responsible for the first cave paintings, he certainly won’t rule out the possibility. “The main point is: we have no clear point of knowing for sure,” he said.

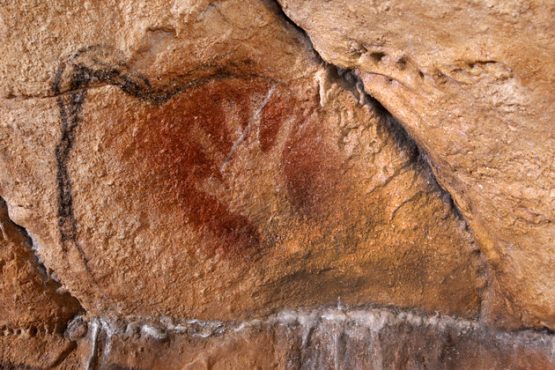

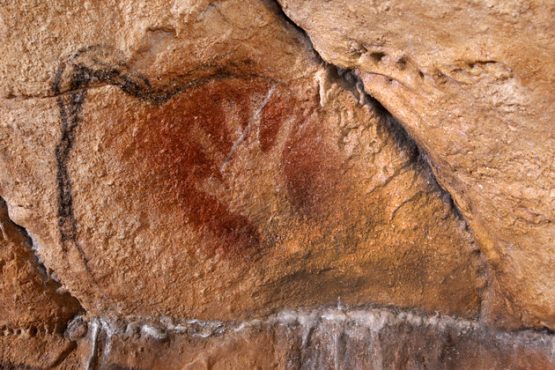

The most convincing evidence positing women as the first cave artists, Whitley believes, are the shapes of the hands imprinted onto the cave walls — the shapes of women’s hands. According to National Geographic, archaeologist Dean Snow of Pennsylvania State University analyzed hand samples from eight cave sites in France and Spain, three-quarters of which were deemed female.

Snow’s study incorporated the findings of British biologist John Manning, who found that while women often have ring fingers and index fingers that are the same length, men primarily have longer ring fingers. And while the ratio isn’t completely consistent when looking at contemporary hands, prehistoric hands are far more sexually dimorphic.

After reading Manning’s study, Snow pulled a book from his shelf with a cover featuring a hand stencil in France’s Pech Merle cave. “I looked at that thing and I thought, man, if Manning knows what he’s talking about, then this is almost certainly a female hand,” Snow told National Geographic.

In Whitley’s perspective, the hand stencil argument presents the strongest evidence that women could be the artists responsible for the cave paintings. However, he isn’t convinced that the women leaving their handprints are the same women creating the artworks. “We don’t know for sure, but it’s certainly possible.”

Snow hypothesized the handprints were an artist signature of sorts, a way of saying “This is mine, I did this.” Whitley, however, isn’t so sure. “Another explanation might be that these were women coming in to see these great works of art and leaving the signs of their visits. They were touching the cave walls and, by that fact, touching essentially the sacred realm.”

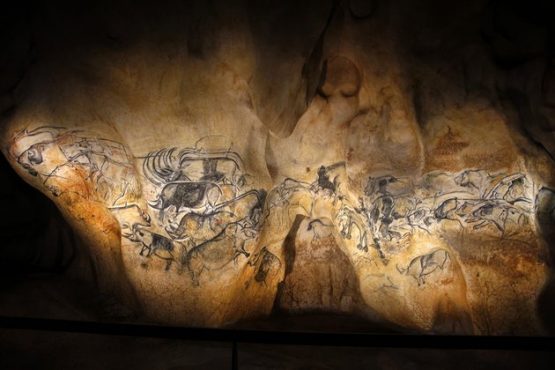

In Whitley’s opinion, there is strong data suggesting that much cave art was created by shamans who entered an altered state of consciousness when inside the caves, serving as proto-sensory deprivation chambers. “What we know ethnographically is that most shamanistic societies — at least in the more recent past — had male shamans. And I say most carefully because not all did. Some certainly had female shamans.”

It’s also possible, Whitley explains, that the handprints were left during initiation rituals led by formal shamans — male or female. “We certainly have ethnographic examples of shamanistic rituals which involve young women,” he said. “Puberty rites, essentially.”

While Whitley is hesitant to deem men or women as primarily responsible for cave art, he’s well aware of the overwhelming feminine symbolism that populates so much cave imagery. “When we look at paintings and engravings, there are images and compositions that point straight at female symbolism of some kind. Chauvet Cave, which has our oldest art at 36,000 years old, is a great example. There we have, in two places, two paintings of horses in these niches in the cave wall that can only be described — it’s pretty obvious and simply can’t be denied — as vaginally shaped. Also, in that same cave, there’s a painting of what’s obviously a woman’s pubic area.”

Yes, lady parts are all over prehistoric caves. But are these artworks empowering self-portraits, odes to female beauty, or something else entirely?

“The relationship between what art portrays and what it symbolizes can be very complex,” Whitley explains, channeling his inner art critic. “This is getting into fairly complex issues, but it recalls what we call symbolic inversions — examples where males use female symbolism. This tends to occur because of the ideological structure of the society. For example, an androcentric view of society where men are controlling women’s reproductive rights, if you will. This is the Republican party today. They don’t do it symbolically, like perhaps the cave artists did, but they’re still trying to do it.”

So, prehistoric cave artists could have been early feminist art makers, painting their vulvas in vaginal cave niches and slapping their handprint proudly aside them. Or they could have been cavemen predecessors of Richard Prince, appropriating the female body for their own artistic purposes.

Either way, a giant looming question mark remains: We may never know what shamanistic rituals or artistic rites went down in those caves some 36,000 years ago. But just because men dominate the art world narrative now, let’s not presume prehistoric people were so predictable.

By Priscilla Frank

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/lets-stop-assuming-the-early-cave-painters-were-dudes_us_561e6ebce4b050c6c4a39bf3